George Fred Keck's House of Tomorrow, built for the 1933 Century of Progress International Exposition in Chicago, will soon be restored. The structure, which now resides in northern Indiana, has been in shambles for years. It's a major building in the history of passive solar heating, as I explain in The Solar House.

Yesterday, the restoration team was formally announced by Indiana Landmarks. Here is the full press release.

For immediate release

March 15, 2017

House of Tomorrow restoration team announced

CHICAGO – At a monthly talk sponsored by AIA Chicago’s Historic Resources Committee, Indiana Landmarks and the National Trust for Historic Preservation announced the team that will lead the rehabilitation of The House of Tomorrow. Designed by Chicago architect George Fred Keck for the 1933-34 Chicago Century of Progress World’s Fair, the building sits in a dilapidated state atop a sand dune in Northwest Indiana.

Todd Zeiger, director of Indiana Landmarks’ northern office in South Bend and House of Tomorrow project manager, introduced the team after the talk on Tuesday, March 14. Jennifer Sandy, senior field officer of the National Trust, also spoke at the AIA session. Last fall, the National Trust named the site a National Treasure and with Indiana Landmarks launched a $2.5 million campaign to restore the house.

The design team working to rehabilitate America’s first glass house includes the following Chicago-based firms.

bKL Architecture taking the lead in architecture and interior design with a team led by Charles R. Hasbrouck, FAIA; Bauer Latoza Studio, led by Edward Torrez RA, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, providing historic preservation consulting services; Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc., providing structural engineering services with a team led by Senior Associate Michael Ford; Willoughby Engineering, led by Thomas Willoughby, supplying mechanical, electrical and plumbing engineering services; HJKessler Associates, led by Helen Kessler, FAIA, LEED, providing sustainability consulting services.

Staff from the National Park Service and State Historic Preservation Office will ensure the project meets preservation standards.

In the midst of the Great Depression, the House of Tomorrow offered 39 million World’s Fair visitors an optimistic look into the future of residential architecture and modern technology, with a focus on how advancements in science and technology could improve daily life. Indiana Landmarks, a nonprofit preservation organization headquartered in Indianapolis, aims to restore the House of Tomorrow while sharing Keck’s goal of making it a visionary dwelling, this time for the twenty-first century.

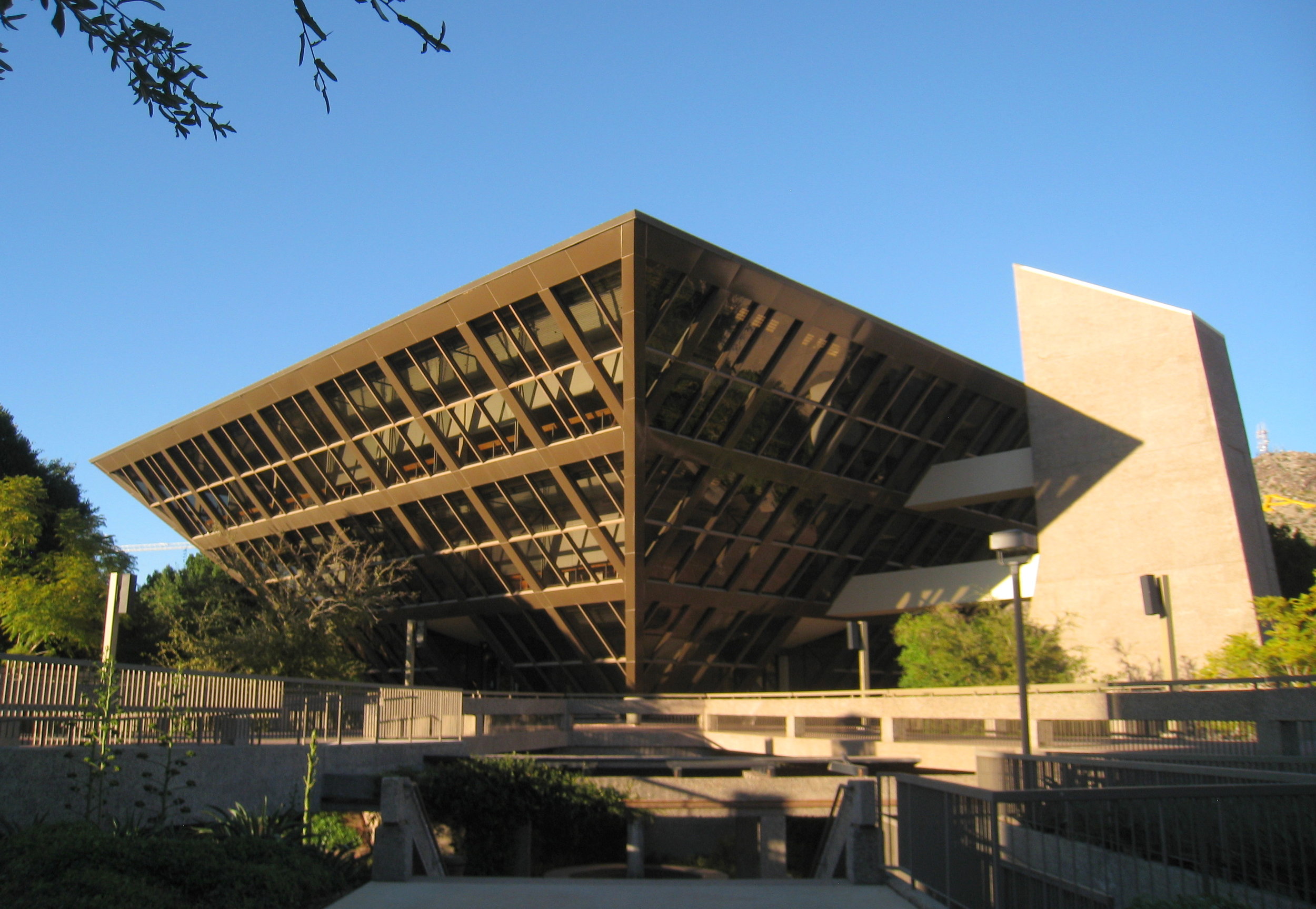

In his design for the House of Tomorrow, Keck underscored the fair’s theme by showing people a new way to live in what the media called “America’s First Glass House.” The glass curtain-wall structure predates Mies van der Rohe’s 1951 Farnsworth House in Illinois and Philip Johnson’s 1949 Glass House in Connecticut.

The large expanses of glass introduced the concept of passive solar energy as a sustainable heating technique for the first time. Four years later, Keck developed Thermopane glass with the Libbey-Owens-Ford company. In his long career—he died in 1980—he designed 300 passive solar houses, most in the Chicago area.

Keck also introduced new inventions and modern conveniences in the House of Tomorrow, including an “iceless” refrigerator, the first-ever General Electric dishwasher, and an open floor plan—an innovation in 1933.

To create the twelve glass sides, Keck designed a central hub of posts connected to girders that radiated like the spokes of a wheel. A central steel core contained mechanical equipment. The cantilevered girders provide support for the concrete-slab second and third floors, along with slender steel columns, allowing clear spans for open interior spaces. The rehabilitation will peel away deteriorated surfaces to reveal the original wheel-and-spoke steel structure, and restore the house using smart glass and other cutting-edge technologies and products.

When the World’s Fair closed in 1934, Chicago developer Robert Bartlett used barges and trucks to ship the House of Tomorrow and other Century of Progress structures to Beverly Shores, an Indiana town he was attempting to develop as a vacation destination for Chicagoans. Five Century of Progress houses were sold and remained in private hands until the land became part of the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore between 1966 and the early 1970s.

All five were listed in the National Register of Historic Places in the 1980s, but by the mid-1990s the homes were in alarmingly poor condition. Since there was no public money to restore the houses, Indiana Landmarks proposed a solution that hadn’t been previously considered: long-term leases.

Indiana Landmarks leased the Century of Progress houses from the National Park Service, and over the last 15 years has subleased four of the five to individuals who restored them in exchange for a long-term residency. The restoration cost for each house—borne solely by the sub-lessees—reached over a million dollars. The House of Tomorrow, however, posed unusual challenges and led Indiana Landmarks to tackle the rehabilitation itself.

“With help from the National Trust, we’ve put together a stellar team of Chicago architects, engineers, and preservation and sustainability experts, all of whom are enthusiastic to work on restoring this important Chicago landmark that happens to live in Indiana,” says Todd Zeiger.

To contribute to the restoration of the House of Tomorrow, a rare World’s Fair survivor that will burnish George Fred Keck’s legacy, visit https://www.indianalandmarks.org/about/special-projects/house-of-tomorrow/.

###

About Indiana Landmarks

Indiana Landmarks revitalizes communities, reconnects us to heritage, and saves meaningful places. With nine offices located throughout the state, Indiana Landmarks helps people rescue endangered landmarks and restore historic neighborhoods and downtowns. People who join Indiana Landmarks receive its bimonthly magazine, Indiana Preservation. For information on membership in the nonprofit organization, call 317-639-4534, 800-450-4534, or visit www.indianalandmarks.org.

About The National Trust for Historic Preservation The National Trust for Historic Preservation, a privately funded nonprofit organization, works to save America’s historic places. www.savingplaces.org

About National Treasures

The National Trust for Historic Preservation mobilizes its more than 60 years of expertise and resources to protect a growing portfolio of National Treasures that are threatened buildings; neighborhoods, communities, and landscapes that stand at risk across the country. Our National Treasures program demonstrates the value of preservation by taking direct action to protect these places and promote their history and significance.

About Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore

Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore is one of 413 units of the National Park System ranging from Yellowstone to the Statue of Liberty. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore includes 15 miles of the southern shoreline of Lake Michigan and 15,000 acres of beach, woods, marshes, and prairie in the northwest corner of Indiana. For more information go to: www.nps.gov/indu

JTPR, Indiana Landmarks 1201 Central Ave., Indianapolis, 46202 Indiana, United States

K-4-1517289-6939510-2-69-AV1-6ABC5C9F

Elsewhere:

Crain's Chicago Business, May 18, 2017

Previously on the blog:

A National Treasure: The House of Tomorrow

The House of Tomorrow Postcard

80 years: The House of Tomorrow