The Empty Niche

/Gabriel, twin buildings at Place Louis XV, 1748 (now Place de la Concorde; Hôtel de la Marine and Hôtel de Crillon). source

I’m often struck by the empty niche, a powerful and profound feature in Renaissance, Baroque and Neo-Classical architecture. It could also be called a blind niche or a vacant niche. In many European cities, particularly Paris, you see them everywhere. Ange-Jacques Gabriel’s empty niches at the Place de la Concorde (above) are most notable due to their urban prominence and fine design, but there are hundreds more. Pretty soon, it begins to feel significant when you see a niche with sculpture.

There is almost nothing written about the empty niche by architectural historians. When did this feature, as a purposeful design, first appear? More importantly, what does it mean? Read the great authors and you’ll hardly find a word. How curious it is that such an important architectural detail seems to have been hiding in plain sight!

After much browsing with these questions in mind, I believe Bernardo Rossellino’s façade for the Cathedral in Pienza, 1460, includes the earliest empty niches in Renaissance architecture. But were these intended to be empty, or to hold sculpture? This is unknown. A forthcoming book, Pienza’s Missing Statues, by independent scholar Andrew Johnson, will shed much more light on Rossellino’s design.

Rossellino, Cathedral of Pienza, 1460. source

I believe that Bramante, in the Tempietto (1502), brought the empty niche into full bloom as a purposely-designed, fully-expressed architectural feature. At the Tempietto (below), you can see that the empty niches occur in the lower-level walls as well as in the drum above, and they are forceful. While the emptiness conveys a sense of unfinished work—there seems to be sculpture missing—I believe that Bramante designed these to be left empty.

Donato Bramante, Il Tempietto, Rome, 1502. source

It is often noted by scholars that the Tempietto introduced the ‘High Renaissance’ because of its three-dimensional sculpting, punctuated by the deep shadows in the drum, while earlier works of Renaissance architecture have a flat character.

If I am correct and Bramante gave life to the empty niche, why? And what does it mean? Bramante and other Renaissance artists surely found empty niches in ruined Roman buildings, where sculptures had been removed later. Perhaps Bramante liked the aesthetic of emptiness and sought to capture the quality of ruins in new architecture. Perhaps he wanted to convey a sense of loss or of time passed. (These are tentative interpretations; again, there is virtually no discourse to lean on or against.)

And what does it mean that Andrea Palladio wanted Bramante’s niches to be filled with statuary? That’s how he illustrated the Tempietto for I quattro libri dell'architettura (The Four Books of Architecture), as shown below. Palladio also liked to show ruined classical buildings in a ‘complete’ state. Meanwhile Sebastiano Serlio correctly showed the Tempietto with empty niches in his treatise, normally called On Architecture.

Almost contemporaneously, Jacopo Sansovino designed empty niches in the facade for San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, Rome, (designed 1509; built 1733-38), but I do not find any empty niches in Sansovino’s more notable work in Venice.

In the 1530s-40s, Michelangelo apparently included blind niches, with square heads, at the Medici Chapel (or New Sacristy at San Lorenzo), where they serve to frame central niches which are powerfully occupied (below).

Michelangelo, Medici Chapel, Florence, 1530s-40s. source

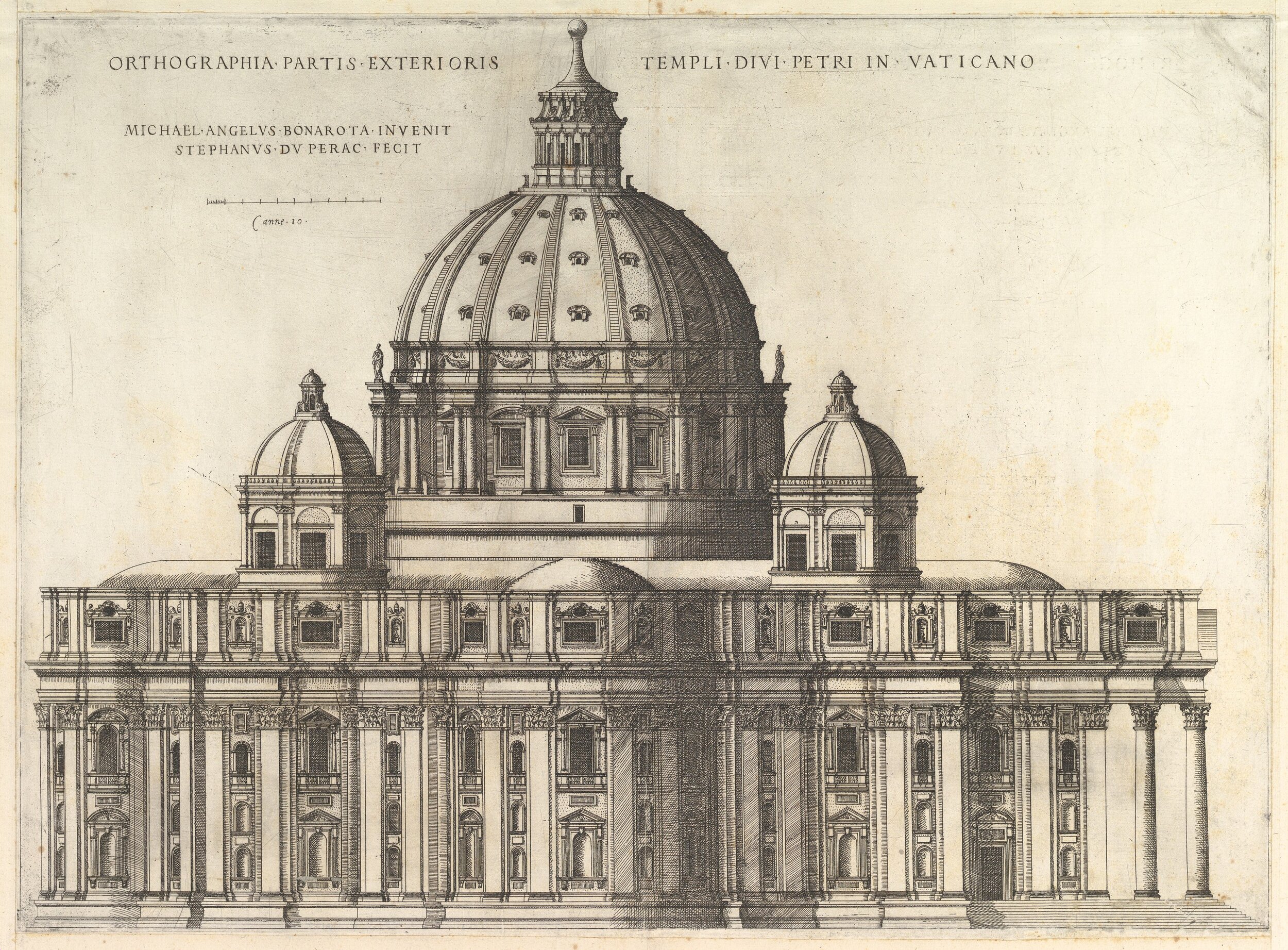

And Michelangelo used empty niches in profusion in the design of the walls around the apse of St. Peter’s Basilica, as seen below in the engraving by Étienne Dupérac. Carlo Maderno followed suit by including empty niches in the façade.

Étienne Dupérac, Saint Peter's Basilica from the South as Conceived by Michelangelo, 1569. source

Again, for emphasis: St. Peter’s Basilica is unquestionably one of the most important and well-known buildings in history. There are empty niches all over it, including in the façade. And yet there is no commentary from architectural historians about this. (Inside St. Peter’s, however, there are no empty niches.)

In the 1580s in England, Robert Smythson included a profusion of empty niches in Wollaton Hall. Smythson had read Serlio.

Further examples go on and on from there, including Borromini at San Carlo, F. Mansart at Val-de-Grâce, and numerous buildings which used Bramante’s Tempietto as a model, like St. Paul’s Cathedral by Wren. Then, followers of Wren in London, and followers of Gabriel in Paris. Since the meanings of architectural features change as they are adapted, we must also consider that the empty niche might have meant something different to Gabriel than it did to Bramante, for example.

● ● ●

Finally I would suggest that the empty niches of and Rossellino and Bramante had an immediate aesthetic precedent in the blind panels found in earlier Renaissance architecture, particularly Brunelleschi’s Pazzi Chapel (below).

Filippo Brunelleschi, Pazzi Chapel, Florence, 1442. source

I take the blind panel and the empty niche to be different features, but strongly related. Brunelleschi would have found blank panels in Roman buildings he studied, like the Pantheon. He also may have been influenced by buildings of the Middle East with patterned panels or screens (but not figural art), such as Dome of the Rock. Certainly the blind panel, like the empty niche, conveys a sense of unfinished work and perhaps the loss of the classical world. (Brunelleschi’s blind panels are often interpreted as conveying the ‘platonic’ beauty of mathematics.)