Solar Geometry in France, 1961

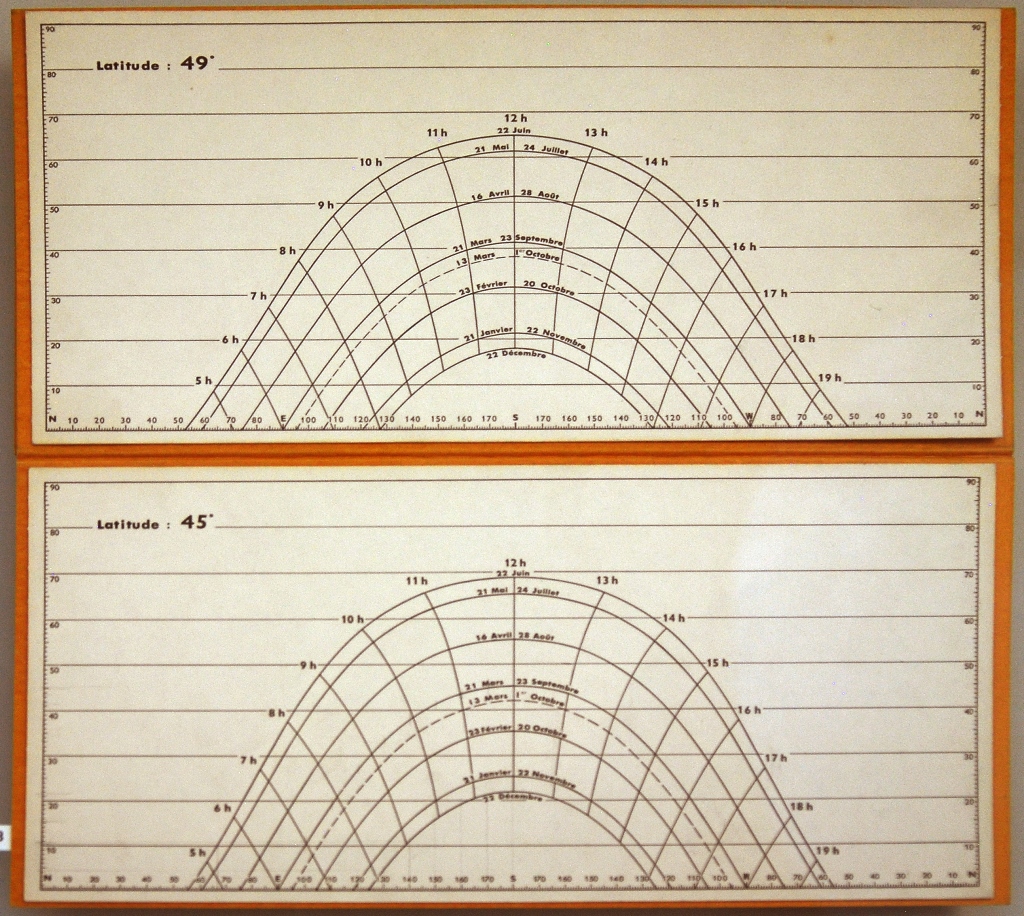

/Even though it’s becoming more and more common to find architectural historians recognizing that environmental concerns were central to the history of modern architecture, the subject of solar heating seems a bit recondite for an institution such as the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine, the major museum of architecture in Paris, which features full-scale Romanesque portals and Gothic sculptures. So I was surprised to find these solar geometry diagrams on display:

At the museum, the caption read: “Diagrammes solaires C.S.T.B.” and no date was given.

C.S.T.B. refers to the Centre Scientifique et Technique du Bâtiment, France's national agency for building science research, then and now. After some further exploration, I believe these diagrams were first published in 1961. The C.S.T.B. researchers, Pierrette Chauvel and Jean Dourgnon, appear to have been important figures in lighting and daylighting research.

Also of note in the image above: the curved lines are at monthly intervals, with the exception of dashed line, which indicates March 13-October 1. I’m not sure why that would have been a significant date. Please comment if you have some insight.

The diagrams were included in a section entitled: “Protectrice et Climatique: Les Vertus de L'Enveloppe.” Here is the explanatory text:

L'une des premières fonctions de l'architecture est de protéger ses utilisateurs du climat extérieur. Une température agréable et constante s'obtient par le choix des magrtériaux de construction, par la conception même du bâtiment et de son enveloppe et, plus récemment, par l'usage de l'air conditionné.

Aux xxe siècle, la façade en verre devient une réalité. Les baies vitrées offrent des vues plus larges sur l'extérieur et une nouvelle perception de l'espace mais laissent entrer une trop grande quantité de rayons solaires. Dans les années 1950, les brise-soleil apportent une solution technique tout en dotant la façade de nouvelles qualités plastiques.

Aujourd'hui, la sensibilisation aux problèmes environnementaux conduit à concevoir une architecture dite <<écologique>>. Le traitement de la <<peau>> entre alors en ligne de compte comme la question des économies d'énergie.

And here as I've translated:

Protection and Climate: The Virtues of the Envelope

One of the primary functions of architecture is to protect users from the weather. A pleasant and constant temperature may be achieved by the choice of building materials, by the design of the building and its envelope, and, more recently, by the use of air conditioning.

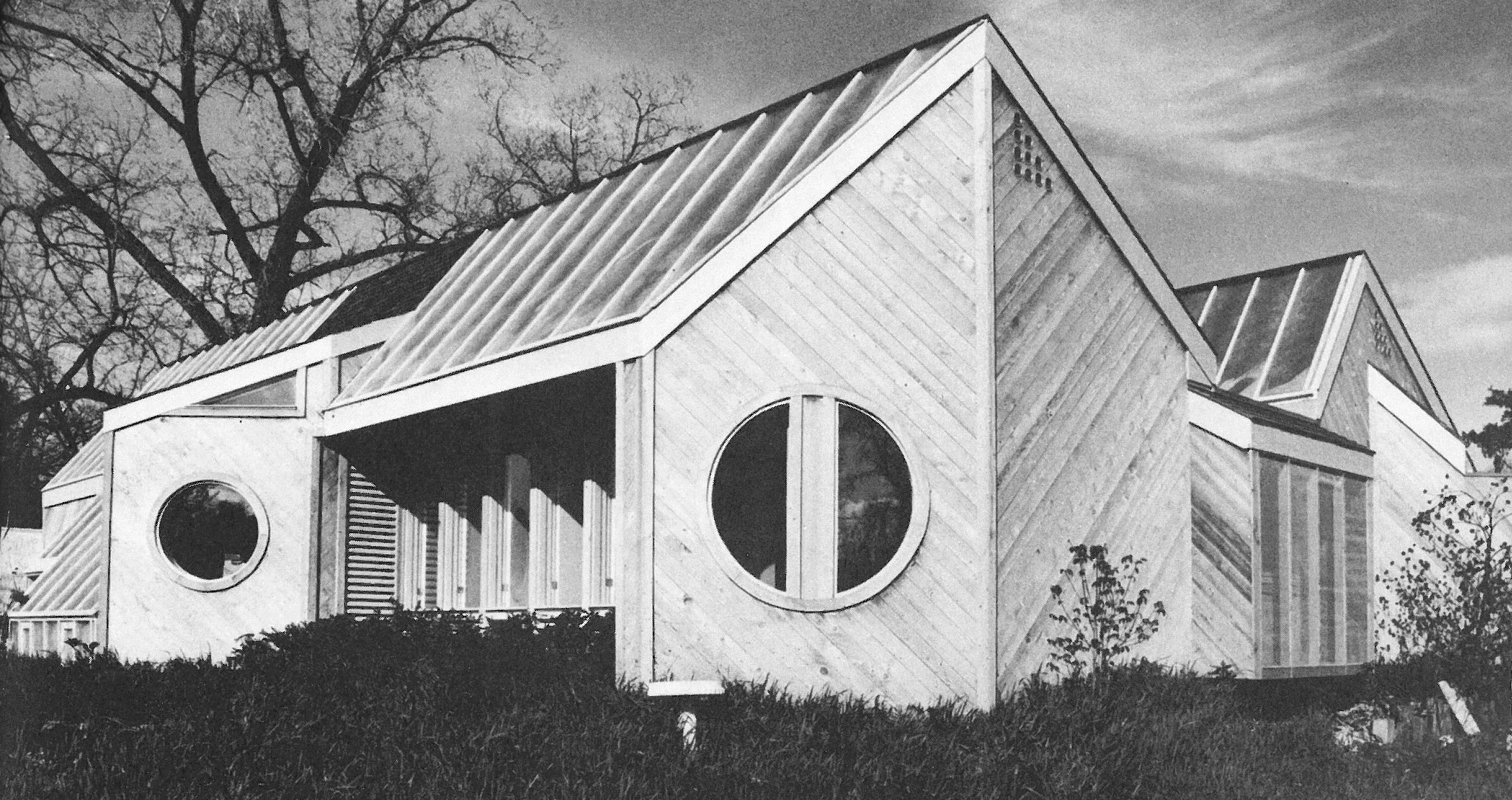

In the twentieth century, the glass facade became a reality. Windows offered a greater views of the outside and a new perception of space but let in too much solar heat. In the 1950s, the brise-soleil provided a technical solution while giving the facade new plastic qualities.

Today, an awareness of environmental problems has prompted an architecture called “ecological.” The treatment of the “skin” then engages the question of energy savings.

In essence, the point of the exhibit is that French modern architects (like Le Corbusier) learned that all-glass structures overheated badly, and that knowledge of solar geometry was needed for proper shading—a major theme in 20th century architecture as I explain in The Solar House.

If diagrams such as those above were only available to French architects beginning in 1961 (and I'm not sure that's the case), then they were a few decades behind. American architects had access to this kind of information in 1938. (See Whit Smith's solar tool.)