Richard Levine: A 1970s Solar Architect

/When you look at solar houses from the 1970s---there were dozens of books which described hundreds of houses---you find a lot of solar architects, often unfamiliar. You wonder what became of them.

One such architect is Richard Levine. I quoted Levine in The Solar House, in an overview of the aesthetic issues in 1970s solar architecture. (The book focuses on solar houses prior to 1973 and only surveys the 1970s briefly.) I included this quotation because I thought it represented a strong idea:

The first steam powered vessels to cross the Atlantic looked like awkward sailing ships not steamships (just as the first automobiles looked like awkward carriages, not Model T’s). They carried a full complement of sails because their reliability was well below 100%. It was not long before they achieved the reliability necessary to evolve their own form and their own structure, vastly different from the form of its progenitors.

Solar building is beginning to embark on this same sort of evolution—awkward, not able to do the job alone, working with adaptations of unsuitable existing forms. The turning point will be when we change our commitment from an add-on, booster mentality to a 100% solar sensibility. At that point evolution will be swift and irreversible. Solar devices, solar buildings and solar villages will rapidly develop appropriate forms and structures.

Then, I wrote: "Such an evolution did not mature in the 1970s."

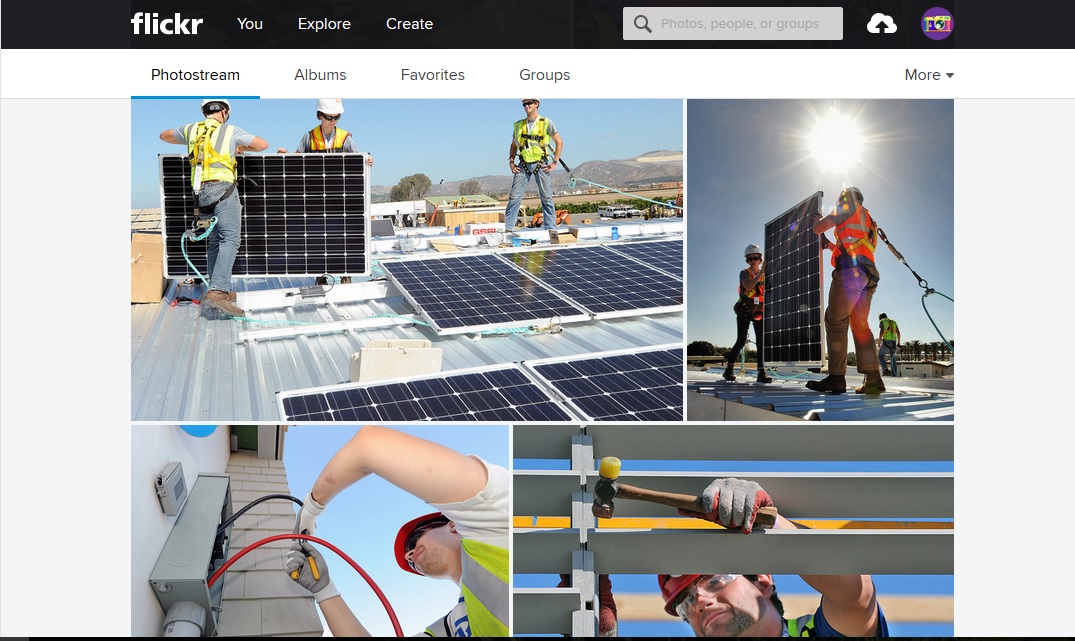

So what became of Richard Levine? He is a professor at the University of Kentucky. Today he was profiled in the Lexington Herald-Leader, featuring his Raven Run house as well as some thoughts about the future of energy-saving homes. It's a excellent piece, because it clearly connects that experimental period, which can seem so remote, with the problems and opportunities of today and tomorrow. I borrowed the photos above from the article.

Link to Lexington Herald-Leader article: "Early solar architect sees big changes ahead for American homes"