Keck's Duncan house: a new look

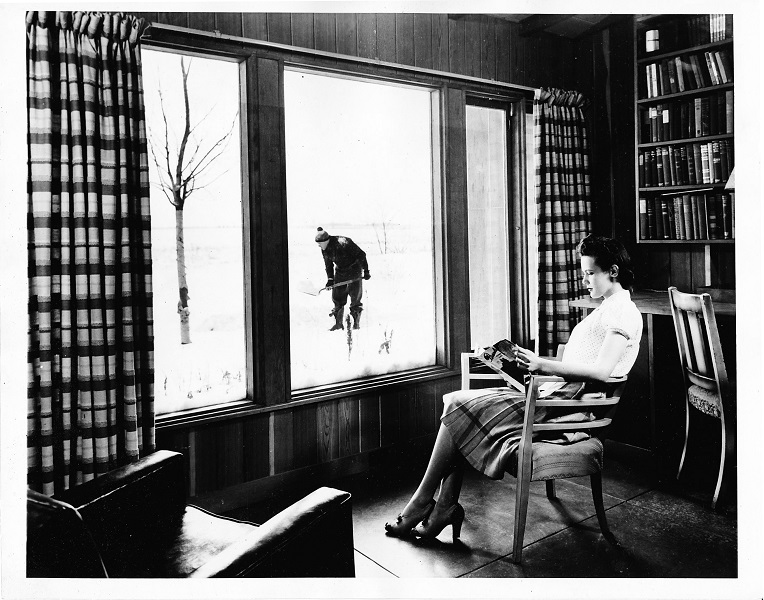

/Here's a rarely-seen period photo of Fred Keck's house for Hugh and Minna Duncan (Flossmoor, Illinois, 1941). In The Solar House the Duncan house is presented in great detail, but this photo did not make it into the book.

Hugh is outside shoveling snow in his winter clothes, while Minna is enjoying the solar-heated living room in her shirtsleeves. Note the concrete floor. You can catch a glimpse of the exterior "adjustable vanes" (for shading) directly above the book Minna is holding, behind the drapes. It's a wonderful artifact from the history of the passive solar house.

Finally, I will note that the caption on the back clearly indicates that the house overheated. Overheating was an important theme in the history of the solar house, and it remains a concern for designers who want to use passive solar and "Passivhaus" methods today. Someone will someday write the history of overheating, and the Duncan house clearly can be a canonical example.

For a bit more on Hugh Duncan and the IIT study of the house, see User Behavior. Incidentally, Duncan was a University of Chicago sociologist, and he wrote a large, fascinating book about architecture: Culture and Democracy: The Struggle for Form in Society and Architecture in Chicago and the Middle West During the Life and Times of Louis H. Sullivan (1965).

Also previously on the blog: Keck's Sloan house II: a new look