A few thoughts on the Architecture of Energy-Efficiency

/For an architect, energy-efficiency and aesthetics are sometimes portrayed as contradictory values. I don’t believe that, at all. But William McDonough and Michael Braungart apparently do:

“Efficiency isn’t much fun. In a world dominated by efficiency, each development would serve only narrow and practical purposes. Beauty, creativity, fantasy, enjoyment, inspiration, and poetry would fall by the wayside, creating an unappealing world indeed.”*

Why do people believe energy-efficient architecture must be ugly? The solar architecture of the 1970s may play a role. I call this the “Age of Aquarius hangover.” The superinsulated architecture of the 1980s also contributes.

But McDonough’s attitude has a more distinguished historic pedigree, I think. Consider Louis Kahn’s quotation:

“Architecture has little to do with solving problems. Problems are run-of-the-mill. To be able to solve a problem is almost a drudgery of architecture. You realize when you are in the realm of architecture that you are touching the basic feelings of man.”

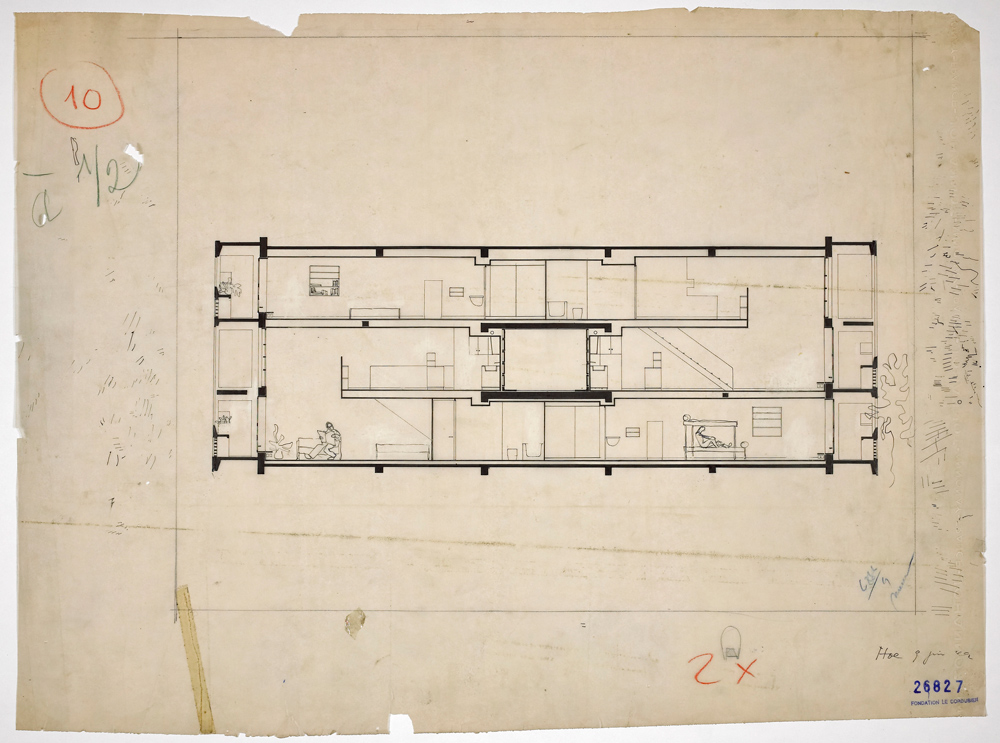

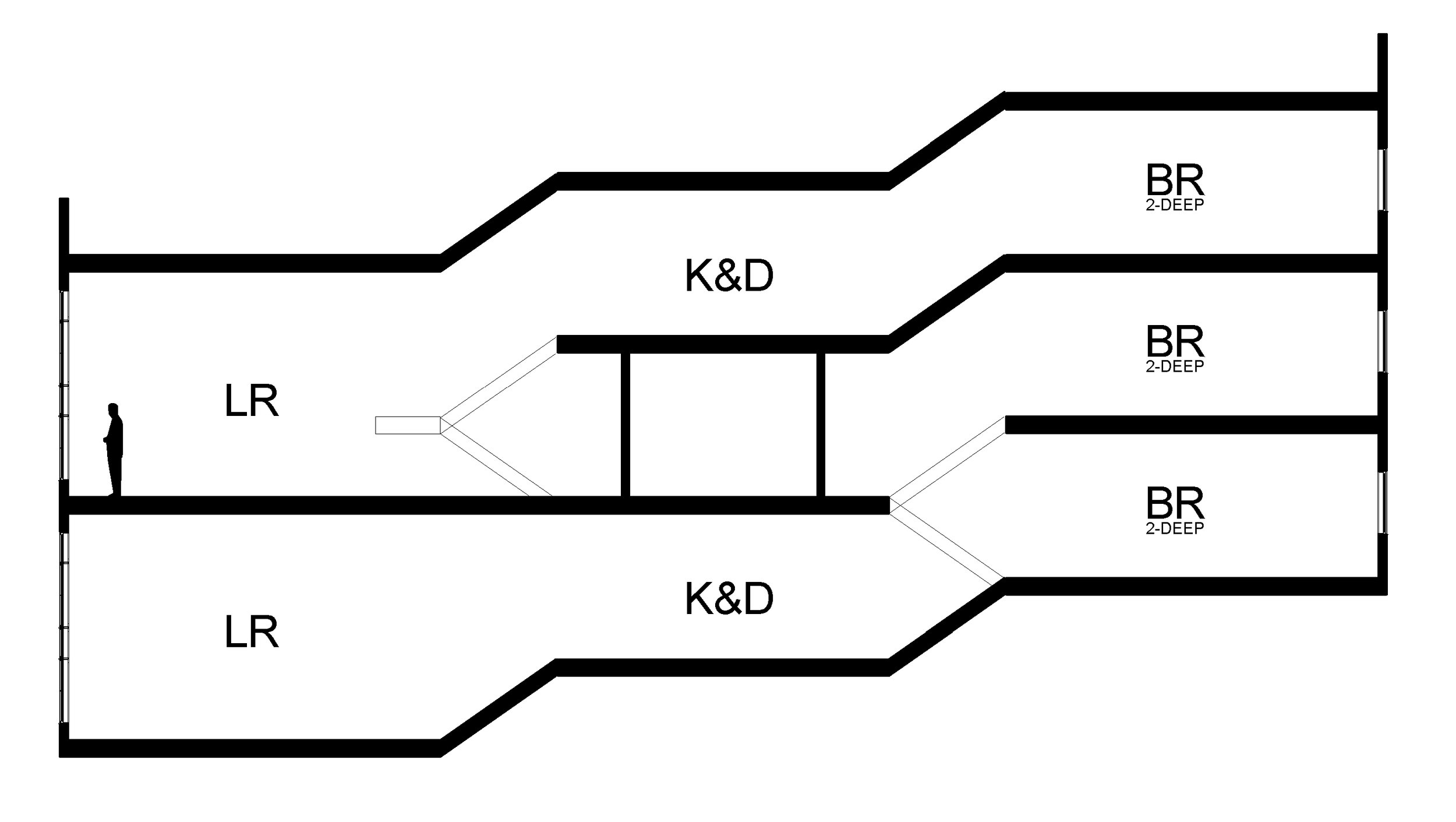

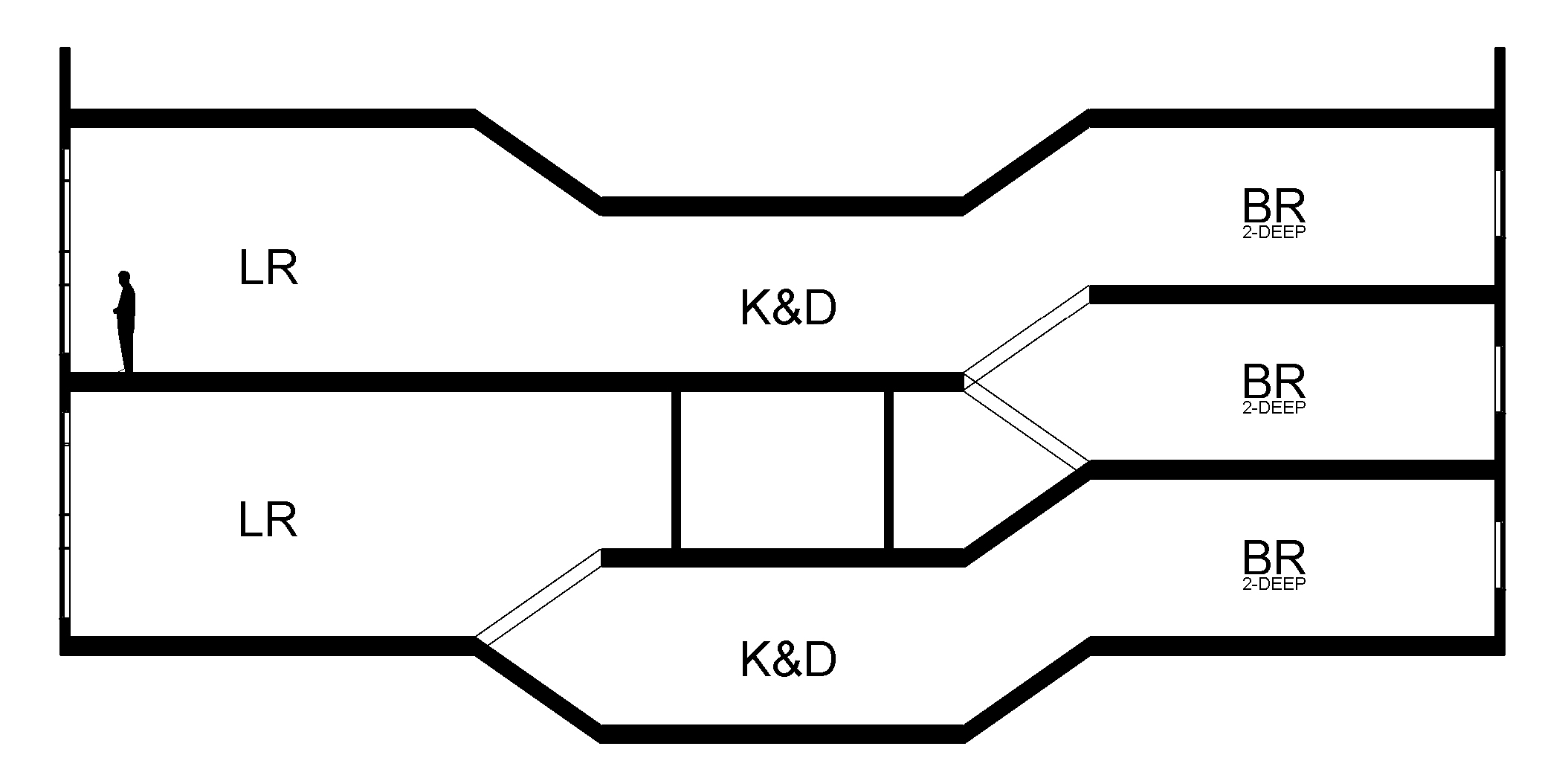

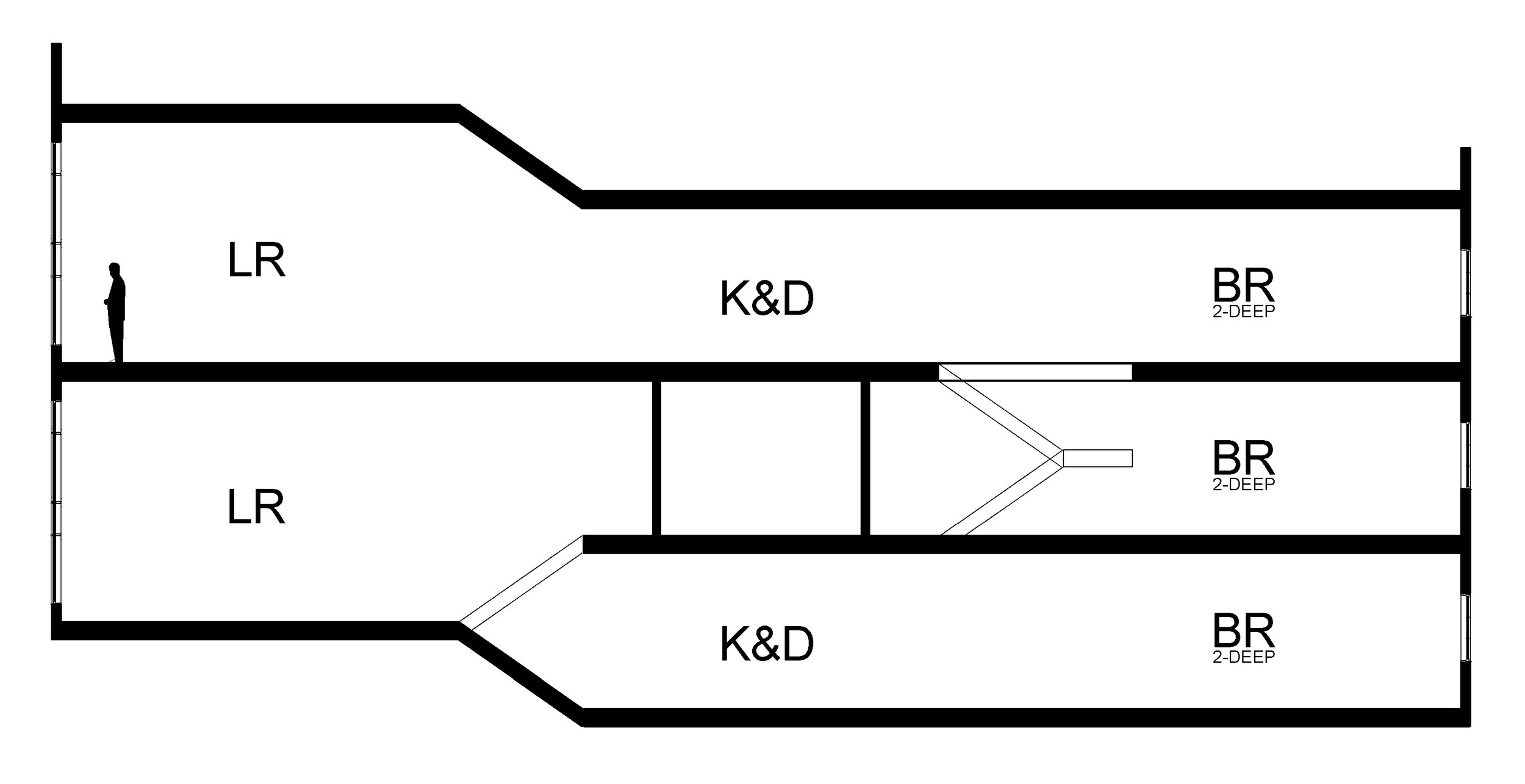

And Kahn’s most important influence, Le Corbusier:

“Works of utility become obsolete every day; their usefulness dies, new utility takes its place. What remains of human enterprise is not what serves, but what creates emotion.”

I believe that designers should be informed by scientific optimization, but not enslaved by it. (My earlier blog entry, Is your window “thermally desirable”? touched on this subject.) In my view, architects always make aesthetic judgments within constraints and contingencies; building energy use is a big one. A good architect embraces constraints and contingencies, and uses them as the basis for expression.

Or, as my eloquent friend Dean Hawkes wrote: “sustainable design in architecture must be as much a cultural enterprise as it is the mechanical observance of a technical principle.”

Please discuss in the comments!

● ● ●

*Hat tip to Peder Anker, who included this quotation in his article “The Closed World of Ecological Architecture.” It comes from Cradle to Cradle, 2002.