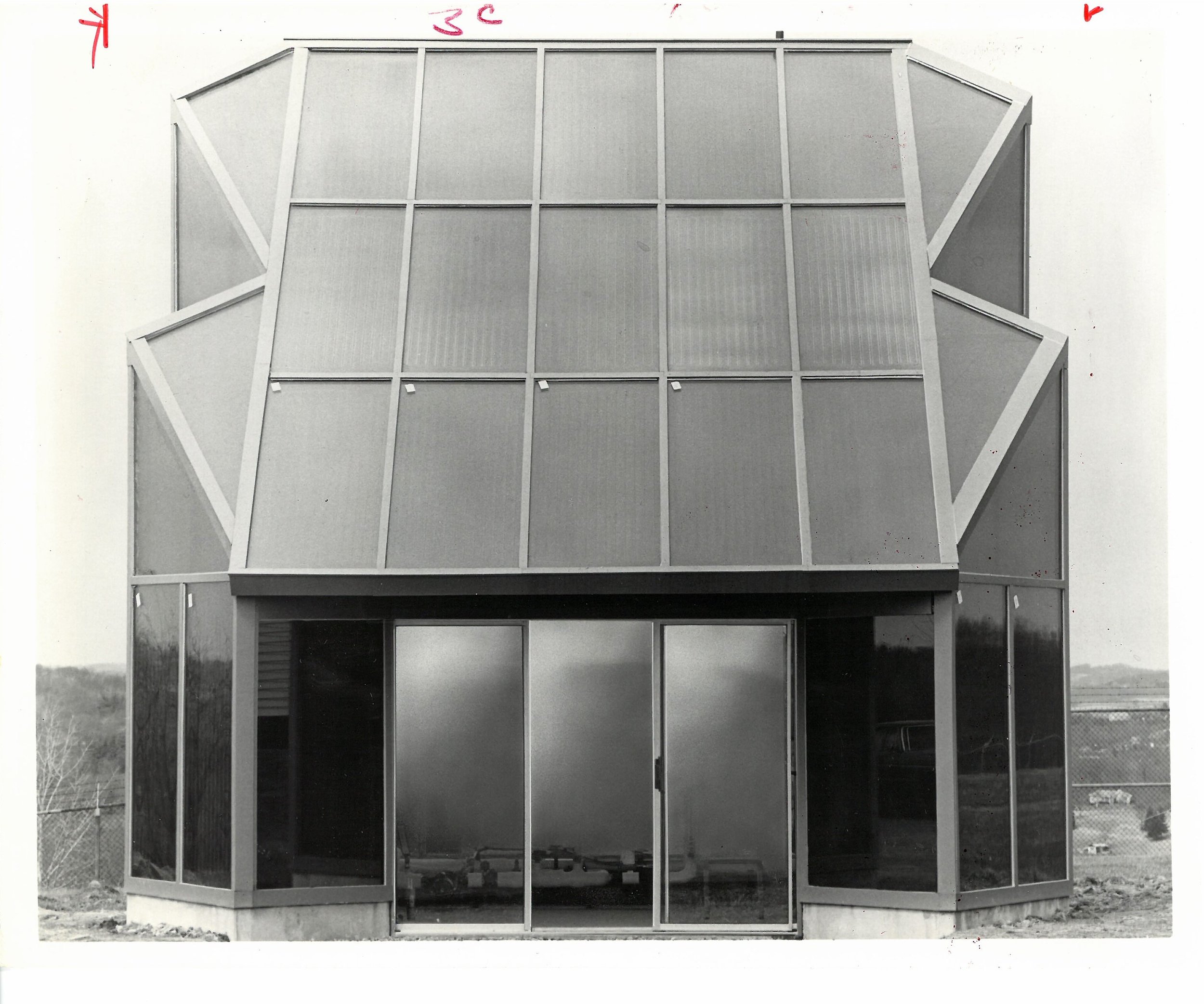

The 1975 PPG Solar Center

/Here's a remarkable building from the history of solar architecture, about which very little is written: The PPG Solar Center (1975) in Harmarville, Pennsylvania. I recently obtained this photo.

This is striking. What a remarkable strength of form and appearance. Is it fair to say, menacing? At a glance, you might be inclined to think this is a photo of an architectural model, but looking carefully at the photo, you can see that it's a real building.

The building's concept may come as a surprise: it was intended to test the possibilities for solar skyscrapers. Basic facts are given in the short Houston Chronicle article pasted to the reverse side of the photo:

SUN MAY 4 1975

NEW SOLAR CENTER

Scientists are monitoring this model energy building at PPG Industries' Harmarville, Pa., research center as a prelude to construction of "solar skyscrapers." This one-and-a-half story structure, which has 27 solar collectors in its roof and walls, is a project of Aluminum Co. of America, Oliver Tyrone Corp., Phelps Dodge Brass Co., Standard Oil Co. of Ohio, Sun Oil and PPG. The project is to demonstrate that solar energy systems can help furnish heating, cooling, and hot water for office and commercial buildings. The projects next phase is construction of an actual sun-fueled office building.

Several other newspapers in the Northeast published the same photo and identical article. An earlier Associated Press article had reported on the corporate partnership and plans for the structure; it was illustrated with an uncredited drawing of a solar skyscraper reminiscent of the Citicorp Center (New York, 1977, architect Hugh Stubbins).*

William Shurcliff included the PPG building in his Solar Heated Buildings: A Brief Survey (13th ed.); it was titled "Learning Model of Tall Office Bldg." Shurcliff reported full technical details; the system used established technologies and products and proven methods. It seems to have been a demonstration more than an experiment.

It does not seem this project was directly related to the Citicorp Center, which had a 45° sloped roof intended for solar collectors, a roof form which remains a characteristic feature of the New York skyline. Citicorp's solar system, which was not built, would have produced hot water, to be used to dehumidify air and reduce cooling energy. An MIT report on the Citicorp solar system mentions PPG as a manufacturer of flat-plate collectors but does not mention this prototype project. And Shurcliff's account of the PPG project (also 1977) does not mention Citicorp, and describes the PPG project as a "pilot project for a later moderate-size bldg. and a still later 6-10-story office bldg."

Nowhere do I find the architect credited. This is unfortunate, because, again, the photograph offers one of the most vigorous and original aesthetic statements in the history of solar architecture.

*printed in the New York Times, August 31, 1974.